| Slovakia Genealogy Research Strategies | ||||||

| Home | Strategy | Place Names | Churches | Census | History | Culture |

| TOOLBOX | Contents | Settlements | Maps | FHL Resources | Military | Correspondence |

| Library | Search | Dukla Pass | ||||

Why Emigrate?

|

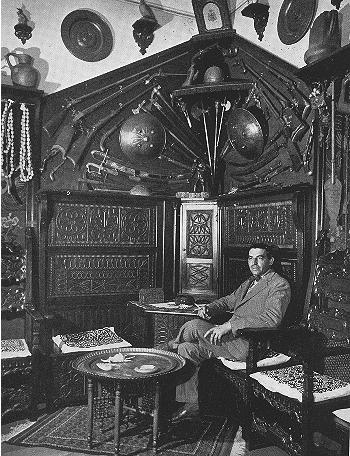

Who lived better? The land baron or his peasant tenants? Do you think they ever met? Who do you think wanted to leave? You be the judge.

There are a lot of misperceptions regarding why people immigrated to America from Slovakia in the early 1900's. Some people believed that they were persecuted, driven from their lands, hated. Others believed that they began to immigrate because places like America were filled with gold for the taking. The truth was simpler: These were people who wanted to survive. Their choice: starve to death due to onerous landlord demands with no opportunity to improve their lot, or move on.

Motivation

The principal reasons were poverty and subjugation.

Poverty - The majority of inhabitants were peasants. Vast lands were owned by barons. In East Slovakia, the baron who owned this property lived in Humenne. The names of the barons changed throughout time, but their treatment of peasants remained the same. The landowners each year asked for greater and greater output. Macartney writes, "The poverty of most of the Slovak peasants is terrifying. Semi-starvation is almost common, actual starvation by no means rare." It was noted in the eighties (1880's) that in many of the Slovak counties the population 'only ate bread on Sundays' and 'meat, practically never';... The staple food was the potato." (Note 1) There was no way to improve the situation.

Subjugation - Virtually all the property was owned by rich, absentee land barons, who continually pressed for greater output. The majority of work was either on the farms or in the forests. Peasants worked so hard that they barely had any time left to improve their own lot. Early to the fields, home for dinner and bed. Church on Sunday was the only break. The landowners only permitted them a small landholding; The emphasis was on maximizing output.

The people were marginalized by the ruling class. Living in the "hinterlands" as one author put it, they were generally unaffected by political struggle and had no nationalistic desires.

Surprisingly, the government policy of "Magyarization" (making all things ethnically Magyar/Hungarian) of the area seemed to have little effect on migration patterns. It appears that the Rusyns were generally known as a submissive, happy-go-lucky race who went along with this process, even to some extent learning the language.

Another ironic twist, was that in spite of it all, they had job security. For life. No that it was worth much to be bound to such a miserable life.

As heartbreaking as it must have been, most immigrants decided to leave rather than starve to death. There was not enough land to produce enough crops for an ever increasing family.

Once the immigration started, stories began to come back about the riches in America. The dream was to go to America, earn enough money to buy their own property and build, and live happily ever after. Many of them did return, those are the stories we have never heard in America. Others sent for their families. Still others stayed in America to start a new life. Little did they realize how two world wars, communism and changing immigration policy would suddenly close the doors to ever go back.

From Where?

Jan Bogardi has done a great job of collecting a few brief maps which illustrate the problem. The first map shows the areas that had the greatest number of emigrants. It included the former Hungary counties of Szepes, Saros, Zemplin and Ung. These were the poorest regions. This is ethnic Rusyn territory, with the Carpathian mountains geographically central. Of course there were several other counties which suffered severe population loss for similar reasons.

So, when you're looking for immigrants from present-day Slovakia, they very well may be noted in the ship manifests as being from Hungary. Also note that in the manifests, most Rusyns were denoted as Ruthenian. Mistakes were oftentimes made and you will see "Slovak" or "Austrian" occasionally.

When?

The period of 1889 to 1913 was the period of greatest emigration. It was around 1889 that the strictest of the "Magyarization" policies came into effect. It ended in 1914 with the outbreak of World War One. Jan's Hungary emigration statistics bear this out.

Why were they resistant to share their past with us?

A common question I hear from everyone. Put yourself in their shoes for a minute. They grew up poor. They lived a relatively miserable village life. They had no worldly possessions, owned no property. They lived in earthen-floor, thatched roof homes, pests scurrying about the walls, floors and ceiling, with a hole in the roof for smoke. In many cases, the animals, their most valuable asset lived with the people. Life expectancy was about 50 years. Working over 12 hours a day six days a week and still not able to make ends meet. Malnutrition and illness; no medical care; superstitions. Illiterate, school ended for most by fifth grade if they were lucky. They might have had the same nice dress or shirt for their entire lives. You eat what you have, with no choice - whatever is available. Meat is a prohibitive luxury. No such thing as idle time. Never was there a thought that you could make life better for your family. The focus was entirely on survival. No transportation - you walked everywhere. "Laborer" or "servant" was the occupation seen most often on ship manifests.

Now contrast this to life in America, even in the 1900s and 1910s. What is there to be proud of? The few skills they had, farming and forestry, were not highly valued. They spoke in an obscure language and worshipped in a misunderstood faith (Greek Catholic). The women and men in America (even the factory workers) dressed in such "fancy clothes" (everything is relative, isn't it?) it made them feel odd. They must have felt ugly, odd, outcast, when so many people passed them by in that fancy dress or suit. They were on the bottom of the social ladder.

Ever notice how many immigrants had vegetable gardens in America? In Slovakia, these gardens were a necessity for subsistence. It was a natural thing to do. Even today, I am asked by Slovakia citizens, "You do have a garden, yes?"

To Stay or Visit?

A surprising number of Eastern/Central European immigrants came to stay but a short time; to earn enough money to take back home to make for a more comfortable life. Especially in the 1900's and 1910's this trend continued. World war I put an end to emigration from 1914 to 1918. In the early 1920's the US Congress severely restricted immigration quotas. During this period, the bulk of immigrants shifted their final destination to Canada, sometimes to France or Argentina. They tended to follow where friends and family had first settled.

World War I and II, immigration quotas and the Cold War severed many the bonds between families. Correspondence continued, but the letters grew shorter as time passed. Less to talk about, the people they knew and loved were passing away.

I have been told stories of immigrants who continued to write letters and hold hope of returning to their homeland some day. One lady speaks of the time when her mother received a letter informing her that her mother had passed away months earlier. After the tears had passed, she abandoned hope and even the desire of every returning.

Their Legacy

As they watched their children grow up, they saw them learn English and aspire to goals of education, reading, writing, work in factories and offices. Joining the military service, joining and embracing American culture. It was a strange and uncomfortable relationship. So their children aspired to these things, bought food from the market rather than grow it in the garden or raise chickens. Their children became "Americans" or "Canadians." Their children bought automobiles, telephones, had electricity, lived in comfortable heated homes.

So as time progressed, their attitude became "who would be interested in the unsophisticated life of a backwoods peasant?" The stories they had were simple, their values in stark contrast to the go-go life of expansionist America. Their beliefs including their customs and superstitions were unappreciated and often scorned at. "These stories would only make people laugh when they find out how little I know."

As the political events churned within their birth lands, it became increasingly complicated to explain their ethnicity, where they were from, what life was like. Even for those who took an interest, answers were confusing and complex. Even the immigrants often didn't understand the changes in Europe.

But for most of us, it was too late to ask and this is what we mostly regret. Take solace though, I'm uncertain that they would even want to talk much if asked.

There is a saying "for a family to immigrate, one generation is lost." What we must recognize is just how much our immigrant ancestors really did sacrifice. It truly permitted their descendants to rise above, to pursue their dreams, to grow, to reach their potential. For this we must be eternally grateful and always remember to light a candle in their memory. I thank them one and all.

References:

Note 1: Macartney, C. A.:

Links to off-site webs will open in a new window. Please disable your pop-up stopper.

Last Update: 15 November 2020 Copyright © 2003-2021, Bill Tarkulich